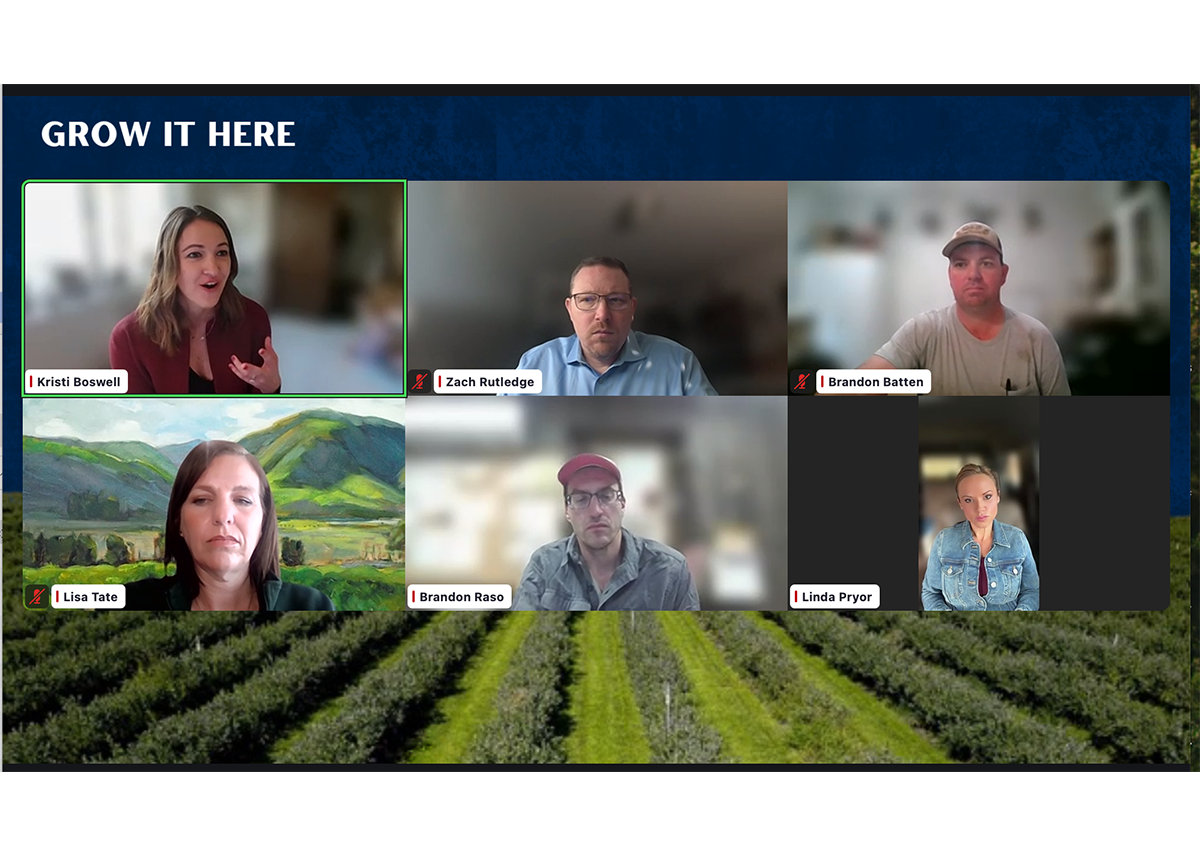

Zach Rutledge, an assistant professor in the department of agricultural, food and resource economics at Michigan State University, joined a panel of growers as part a webinar series from Grow it Here to discuss the impact of labor challenges on the fresh produce industry.

“When you have a decrease in the labor supply, that’s going to put upward pressure on farm wages, it’s going to reduce domestic production and reduce the supply of goods that are produced here in the U.S.,” he says. “Ultimately, in aggregate, when we look nationally, a reduced supply of production means that that’s going to put upward pressure on food prices.”

Rutledge says there are several reasons why there’s a decline in farmworkers from better job opportunities in non-farm sectors in the U.S., to better opportunities in other countries that would supply farmworkers. Immigrant farmworkers who have settled down in the U.S. no longer follow the crops from the south to the north throughout the growing season. And those workers who came to the U.S. in the 1990s and 2000s have not been replaced.

“In the 1990s, there was about 50% to 60% of the workers would migrate at least 75 miles to work on a farm away from their home,” he says. “The share of those workers has just declined since the turn of the millennium. Now we have only about 10% or 15% of the workforce willing to migrate to work on farms.”

He says following interviews of 2,500 growers in California, he’s discovered the average labor shortage is about 20% of growers.

Rutledge also shares his economic model to highlight the link between changes in the specialty crop labor market and food prices.

“When you have a 10% reduction in farm employment, that causes a 2.94% increase in food prices in aggregate across the U.S.” he says. “We have a specialty crop sector that’s worth about $115 billion per year. So, what that translates to is an additional $3.4 billion in food prices.”

Growers’ Perspective

Lisa Tate, a fifth-generation citrus and avocado grower in southern California, discussed some of the challenges of a lack of contracted labor crews. She says when her family requests a crew during a labor shortage, a farm labor contractor might send fewer workers, which slows down harvest and creates a ripple effect throughout her family’s business.

“Packing houses can’t run at full efficiency,” she says. “Fruit isn’t always picked at peak maturity. Other farms wait longer for crews, and most importantly, for the growers, the fruit quality suffers. So lower quality affects grading and ultimately reduces the price farmers receive for their goods.”

Tate says growers can’t stop or slow production, and often in labor shortages, that means crews work overtime, which is extremely costly in the state of California.

“These additional costs don’t get passed along to the retailers and eventually the consumer, because growers often don’t know the price they’ll receive at harvest,” she says. “In many cases, my payment doesn’t arrive until nine months later, which makes it hard to know in real time whether continuing to harvest is financially sustainable. Even if I was able to adjust the price, the higher prices make us less competitive with foreign growers.”

And, she says this takes a toll on growers, who often decide to leave agriculture altogether instead of cutting back.

“The most serious impacts of labor instability build slowly, which is why they’re really easy to miss,” she says. “Crops keep growing, and harvests continue just more slowly and less efficiently, making them even less financially competitive with foreign growers. And the problem doesn’t always immediately show up in the production numbers or at the grocery store, but over time, those effects add up as farmland and farmers are lost.”

Brandon Raso of Variety Farms in Hammonton, N.J., says this past year his family struggled to find enough workers to harvest the blueberries on his family’s 650-acre farm. He says his family typically needs about 600 to 700 workers but could only find about 200 workers.

“I’ve calculated that we lost 2.5 million pounds of blueberries last year due to falling on the ground — just due to the fact that we couldn’t harvest,” he says. “We’ve seen a huge exodus in multigenerational farms in our area. Just in the past two years, we’ve seen three farmers close their doors based off the fact that we can’t find the workers to get the crop harvested.”

Raso echoes what Tate says in that he doesn’t know what the end price will be.

“We’re price takers, not price makers, which is always an important thing to remember with all commodities, for the most part,” he says. “At the end of the day, whether I produce a million pounds or 10 million pounds, I don’t dictate the amount of money that I bring back to the farm to keep us sustainable year to year.”

What About Mechanization?

Raso says his family has invested significantly in new plantings, but that will take his family about eight to nine years to be in full production and get a return on the investment. Raso says he’s been asked about investing in new technology and automation to offset the loss of labor. He says with blueberries, there’s so many different aspects from fields to packing.

“The cost is so unsustainable for us to even think about investing in those sorts of systems, that it’s out of the question,” he says. “Farming, in many ways, it’s still such a primitive occupation. You grow a crop, you harvest it, and you ship it, and there’s only a few ways to do that. Yes, things have improved. Technology has improved. It’s definitely aided us in being competitive. But, you know, at the end of the day, if you have a T-shirt factory and no workers show up, how many T-shirts can you make? None. Why? Because you still need people there to turn the equipment on. You still need people to open the doors, turn the lights on. In most cases, it comes down to the number of people you have to operate that business.”

Linda Pryor, a third-generation apple grower from Hilltop Farm in Hendersonville, N.C., agrees, noting her family has used as much mechanization as possible.

“If there is an opportunity to mechanize, we have used it because the labor is so expensive,” she says. “Any type of reasonable machinery is going to pay for itself really quickly. And additionally, there’s just places that these machines can’t get to. I don’t farm on flat ground. I farm on hillsides. And so having machinery that is capable of doing that, and even if those types of machines existed, which they don’t, it would be really difficult for them to get into a lot of the places, so wherever possible, we definitely do mechanize, but there’s just a lot that just needs people.”

Upfront Costs to Growers

Tate says her family sends the picked fruit to the packinghouse that washes and stores it and then sells it. Tate says her family pays all the costs up front without knowing what the end return will be.

“The way that it works is, whatever the money [the packinghouse gets], everybody gets paid in the process,” she says. “Whatever is left over is what the farmer gets. And sometimes that’s good, you get a lot of money, and sometimes you end up owing money at the end of it. You don’t know until much later in the season that that’s what it is.”

And she says it might take multiple bad years before growers give up.

“You have to remember that we’re on an 80-year life cycle with some of our trees,” she says. “If we’re taking out some, maybe we invested in 20 years ago, we still haven’t recouped the cost of that investment for 20 more years. If we make that really tough decision to remove that crop and replace it with something, it’s a huge loss.”

Brandon Batten, a sixth-generation blueberry grower from Triple B Farms in Johnson County, N.C., says a lot of his family’s returns are based on supply and demand. Once crews harvest the blueberries and they’re in the cooler, his family starts making calls.

“If there’s a lot of blueberries in the market, your price is going to be a little bit lower,” he says. “If there’s a little bit of an opening, we make a few more bucks. But at the end of the day, there’s never the decision to say, ‘hey, let’s, let’s hang back a couple days,’ or ‘let’s put it off and maybe come back next week and see what we got.’ Once the crops are on, it’s seven days a week until the season is over a couple of months later.”

Batten also says his family fronts the costs of the labor, materials and packaging, and he says his family often won’t see payments for 60 days.

“It’s always nail-biting,” he says. “You know, once the season is over and the smoke settles, you see what you’re left with. And you know, hopefully you have a few bucks to make a few investments and get ready for next year.”